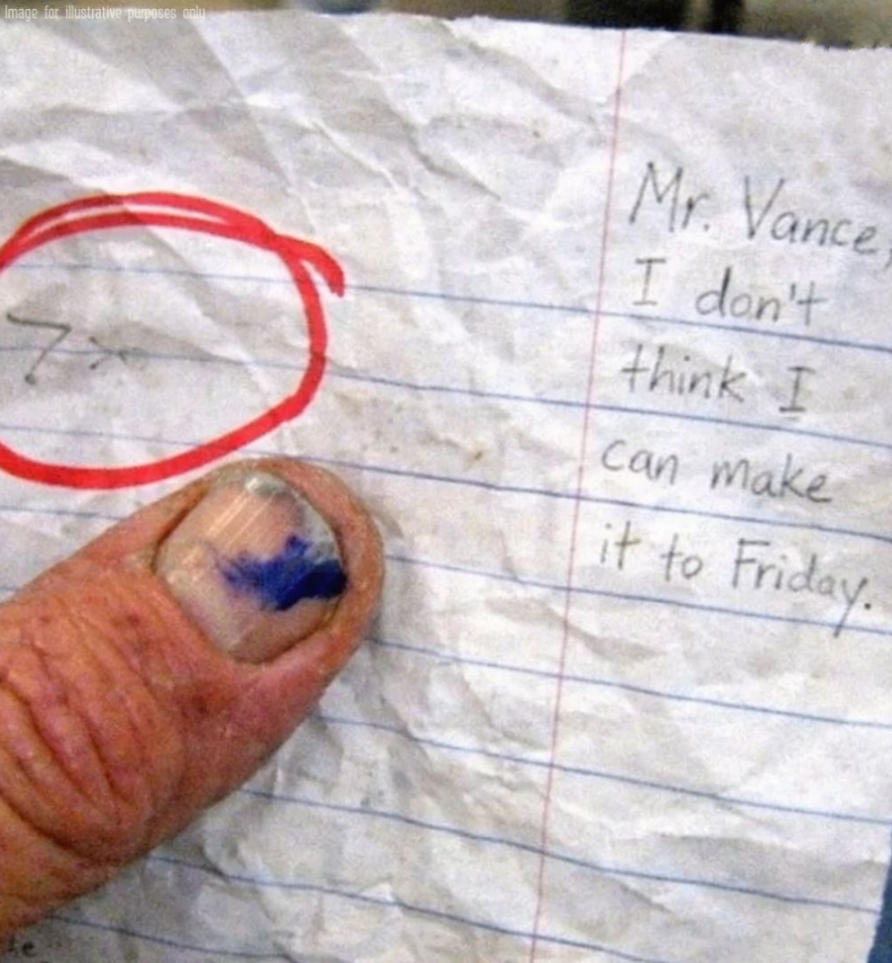

The note that saved a boy’s life wasn’t flagged by a safety algorithm. It wasn’t caught by a keyword filter. It was scribbled in faint, erasable pencil on the back of a pop quiz, invisible to a scanner, right next to a wrong answer about The Great Gatsby.

If I had done what the district wanted—if I had used the “auto-grade” feature on the new tablets—that quiz would have been processed in three seconds. The boy, a quiet sophomore named Leo who wore the same gray hoodie every day, would have received a 60%. The system would have recommended remedial reading modules.

But I don’t use the auto-grade. I use a red felt-tip pen. And because I was looking at the paper with my own tired, straining eyes, I saw the tiny, trembling letters Leo had written in the margin: “Mr. Vance, I don’t think I can make it to Friday.”

I was thinking about Leo as I sat in the windowless auditorium of the district headquarters. The air conditioning was humming a low, aggressive drone that made the room feel like a meat locker.

On the stage, a man named Dr. Sterling was pacing back and forth. He was our new Superintendent of Innovation. He wore a smartwatch that probably cost more than my first year’s salary, and he spoke with the energetic bounce of a man who had never tried to teach Romeo and Juliet to a room full of hungry, heartbroken teenagers on a rainy Tuesday.

“The future of education is frictionless,” Sterling announced, clicking a remote. A massive graphic appeared on the screen behind him. It showed a student’s head connected to a cloud icon. “With the rollout of ‘Apex-Learning 4.0,’ we are finally eliminating the bottleneck of human delay. The AI assesses proficiency in real-time. It creates a personalized pathway. It frees you, the teachers, from the drudgery of grading so you can focus on… facilitation.”

Facilitation. That was the new word. We weren’t teachers anymore. We were “Instructional Facilitators.”

I looked down at my hands. They were stained with blue ink from my fountain pen. I’m sixty-two years old. I have chalk dust permanently settled in the creases of my knuckles. I’ve taught in this district for thirty-five years. I remember when we had textbooks that fell apart if you opened them too fast. I remember when we had to buy our own fans in September.

But mostly, I remember the kids.

I looked around the room. Three hundred teachers sat in silence. I saw Sarah, a brilliant history teacher, rubbing her temples. I saw David, a math wiz who used to play guitar for his homeroom, scrolling through job listings on his phone under the table. We were all demoralized. We were being told that our intuition, our experience, and our connection to the students were “inefficiencies” to be optimized out of existence.

“By shifting to this adaptive model,” Sterling continued, his voice booming, “we project a 30% increase in standardized test throughput and a significant reduction in staffing costs over five years. We are removing the variable of subjective bias.”

Subjective bias.

That was the phrase that made me stand up.

My lower back popped. My knees groaned. I wasn’t trying to make a scene; I just couldn’t sit there and let him call my life’s work a “variable.”

“Excuse me,” I said. My voice wasn’t loud, but in the dead silence of that room, it carried.

Dr. Sterling stopped mid-stride. He looked at me, shielding his eyes from the stage lights. “We’ll have a breakout session for questions later, sir.”

“I’m not asking a question,” I said, stepping into the aisle. “I’m offering a correction.”

I walked toward the front. I don’t walk fast these days, but I walk with purpose. I could feel the eyes of the young teachers on me—the ones who are drowning in paperwork and fear, the ones who are quitting within their first three years.

“You used the word ‘bias,’” I said, facing the stage. “And you talked about ‘frictionless’ learning. I want to tell you about friction.”

I turned to look at the room, then back at Sterling.

“Last week, I assigned an essay on To Kill a Mockingbird. A student submitted a paper that was perfect. The grammar was flawless. The structure was impeccable. The thesis statement was strong. Your ‘Apex’ system would have given it an A-plus instantly.”

I paused.

“I gave it a D.”

Sterling smirked. “Well, that sounds like exactly the kind of subjective grading we are trying to eliminate.”

“I gave it a D because it wasn’t his voice,” I said, my voice rising. “I’ve known this student for two years. I know he loves baseball and hates adverbs. I know he struggles with run-on sentences when he gets excited. The paper he turned in was generated by a chatbot. It was soulless. It was technically perfect and humanly empty.”

I took a breath.

“So, I didn’t grade it. I sat him down. I created ‘friction.’ We talked for an hour. I found out his parents are going through a violent divorce and he hasn’t slept in three days. He used the bot because he was too exhausted to think. We didn’t talk about the book. We talked about how to survive the night. I got him to the counselor. He cried. I listened. That is the job.”

I pointed at the giant screen behind Sterling, at the cold, clean lines of his data graph.

“Your software can count how many commas a student uses. But can it tell if a child is hungry? Can your algorithm detect the difference between a student who is lazy and a student who is working a night shift to help pay their family’s rent?”

The room was electric now. The silence had changed. It wasn’t the silence of boredom anymore; it was the silence of people holding their breath.

“You want to prepare them for the real world?” I asked. “The real world is terrified. The real world is lonely. These kids are growing up in a time where everyone is shouting and no one is listening. They are addicted to screens that tell them they aren’t good enough. The last thing—the absolute last thing—they need is another screen judging them.”

I looked at the young teachers in the front row.

“They need eye contact,” I said softly. “They need to see us make mistakes on the whiteboard. They need to see us laugh. They need to know that when they fail, a human hand will be there to help them up, not a notification ping.”

“Sir, you are out of order,” Sterling snapped, his smile gone. “This is a mandatory training on district policy.”

“It’s a funeral for the profession,” I said. “And I won’t be a pallbearer.”

I picked up my bag. It was an old leather satchel, battered and scratched, filled with unread essays and half-eaten apples.

“I’m going back to my classroom,” I said. “I have a stack of journals to read. Hand-written. Illegible. Messy. And beautiful. Because that’s where the truth is. The truth is in the margins.”

I turned and started the long walk up the aisle toward the exit doors.

For five seconds, the only sound was my footsteps on the carpet.

Then, I heard it.

Snap.

It was the sound of a notebook closing.

I heard the squeak of a sneaker. Then the clatter of a chair.

I didn’t look back, but I could hear them. One by one, then ten by ten. The rustle of coats. The zipping of bags. The English department. The Science department. The Special Ed teachers who have the hardest job on earth.

They were standing up.

When I pushed open the double doors into the hallway, a young woman caught up to me. It was Ms. Miller, a second-year teacher who I knew had been crying in her car during lunch breaks.

She was trembling, but her head was high.

“Mr. Vance,” she whispered. “I was going to quit today. I had my resignation letter in my bag.”

She reached into her purse, pulled out a crisp white envelope, and ripped it in half.

“I thought I was failing because I couldn’t keep up with the data entry,” she said, tears welling in her eyes. “I forgot why I wanted to do this.”

I smiled at her. It was a sad smile, but it was genuine.

“We can’t stop the future, kid,” I told her. “The tablets are staying. The budget cuts are staying. The world is getting faster and colder.”

I put a hand on her shoulder.

“But a machine cannot build a legacy. A microchip cannot comfort a child who has just had their heart broken. That is our territory. We are the keepers of the light. Don’t let them dim you.”

We walked to the parking lot together. The sun was setting, casting long, golden shadows across the asphalt. It looked like the end of something, but for the first time in a long time, it also felt like a beginning.

Here is what we must remember:

We are building a society obsessed with speed, metrics, and optimization. We want education to be downloadable and success to be quantifiable.

But you cannot automate inspiration. You cannot optimize the spark that happens when a child finally understands a concept they’ve been fighting for weeks.

When a student looks back on their life, they won’t remember the educational software that tracked their reading speed. They won’t remember the frictionless interface.

They will remember the teacher who noticed they were fading. They will remember the adult who looked them in the eye, ignored the bell, and asked, “Are you okay?”

Technology is a tool. Teachers are the heartbeat.

Let’s stop trying to code the humanity out of our classrooms, and start fighting for the connection that makes us human in the first place.

PART 2 — “The Day the Speech Went Viral (and the Kid I Was Trying to Save Disappeared)”

By the time I got home that night, my old flip-style phone—yes, I still carry one—was vibrating itself off the kitchen counter.

It wasn’t one call.

It was a swarm.

Voicemails. Texts. Emails I didn’t know I could receive on a device that simple.

And one subject line, repeated like a chant:

YOU’RE TRENDING.

I stood there in my dim kitchen, still smelling like auditorium carpet and stale coffee, and stared at my hands like they belonged to someone else.

They were still stained with ink.

Proof that I had done something stubbornly human in a world that wanted everything clean and automatic.

I didn’t “go viral” because I said something clever.

I went viral because someone filmed an old teacher walking out like he was walking out of his own funeral.

Someone had clipped my speech into thirty seconds. Then fifteen. Then eight.

A grainy video of me pointing at that giant data graph.

My voice, cracked and furious, saying:

“The truth is in the margins.”

People love a quote.

They love a villain.

They love a hero even more—until the hero inconveniences them.

I opened my laptop—an old one with a sticky “I ❤️ BOOKS” decal on the lid—and watched the clip play on loop.

Comments poured in beneath it like rainwater finding every crack.

Half of them made me want to laugh in disbelief.

The other half made my stomach sink.

“He’s right. My kid needs a human.”

“Old man is scared of technology.”

“Teachers are biased. Machines are fair.”

“Machines are biased too—just better at hiding it.”

“If he cared so much, why are his students failing tests?”

“If he cared so much, why didn’t he retire?”

And then the one that hit like a slap:

“So he refuses to use safety tools… and he’s proud?”

That’s the thing about the internet.

It can turn a lifeline into a courtroom in under an hour.

I closed the laptop.

Not because I couldn’t handle the criticism.

I’ve been criticized my whole career—by parents, principals, teenagers with sharp tongues, and my own conscience at three in the morning.

I closed it because I suddenly saw Leo’s quiz again.

That faint, trembling pencil.

Mr. Vance, I don’t think I can make it to Friday.

And I realized something terrifying:

While strangers argued about my “hot take,” a quiet boy in a gray hoodie might be running out of days.

The next morning at school, the hallway felt like a different planet.

Teachers weren’t just nodding at me anymore.

They were staring.

Some with admiration.

Some with panic.

Some with the tight, resentful look of people who think you just made their lives harder.

Ms. Miller found me by my classroom door, eyes wide.

“They’re saying the district is furious,” she whispered.

“Of course they are,” I said, unlocking the door with a key that still had the old school logo on it—back when we believed a logo meant pride, not branding.

She swallowed.

“People are calling you… brave.”

I hung my coat.

“They’ll call me worse by lunch.”

She gave a shaky laugh, then hesitated like she was about to confess something.

“They also said,” she murmured, “that Dr. Sterling is scheduling ‘compliance meetings.’ For anyone who walked out.”

The word compliance landed heavy.

Like a hand pressing down.

Like a reminder that courage doesn’t pay the electric bill.

“Where’s Leo?” I asked.

Ms. Miller blinked. “Leo?”

“Second period.”

“Oh.” Her face shifted. “I don’t know.”

I checked my roster on the district portal—another screen, another login, another password I could never remember without writing it on a sticky note like a criminal.

ABSENT.

I stared at the word longer than I should have.

Absent could mean overslept.

Absent could mean sick.

Absent could mean he was sitting in the nurse’s office pretending his stomach hurt because it’s easier than saying his heart does.

Absent could also mean something else.

Something quiet.

Something final.

I set my bag down and pulled out the quiz.

I didn’t need to. I had already memorized the message.

But I did anyway, like touching a bruise just to confirm it’s real.

Then I did the thing the district hates most.

I acted before a form told me to.

I walked straight to the counseling office.

Ms. Ruiz, the school counselor, was the kind of adult every kid deserves and very few get: warm without being fake, firm without being cruel.

Her desk was covered in sticky notes and small rubber stress balls shaped like fruit.

A jar of pens with little motivational quotes taped to them.

A sign that said: YOU ARE NOT A PROBLEM TO BE SOLVED.

I held out Leo’s quiz like it was fragile glass.

Her eyes dropped to the pencil message, and the air changed.

No dramatic gasp.

No cinematic clutching of pearls.

Just the quiet, professional stillness of someone who’s seen this before.

“How long have you had this?” she asked.

“Since Friday,” I said. “I… I saw it in the margin.”

“And you didn’t file it through the system?” Her tone wasn’t accusing. It was simply factual.

“The system wasn’t involved,” I said. “It would’ve missed it.”

She exhaled through her nose, a slow burn of frustration.

“I need his address,” she said. “Now.”

I gave it to her. I knew it because I know my kids. Not just their grades. Their stories. Their shoes. Their silence.

Ms. Ruiz stood up.

“I’m calling home,” she said. “And I’m notifying the principal. This is protocol.”

“Good,” I said.

Then, because I’m sixty-two and I’ve lived long enough to know protocol doesn’t hug anyone, I added:

“And I’m going too.”

She looked at me, sharp.

“Mr. Vance—”

“Not alone,” I said. “I’m not doing anything reckless. But I’m not staying in my classroom while a kid disappears.”

For a second, I thought she’d argue.

Then she nodded once.

“Okay,” she said. “But we do this together.”

That’s what a real team looks like.

Not a dashboard.

Not a data chart.

Two adults refusing to let a child become a statistic.

We found the principal in his office, sweating through his dress shirt like he’d been handed a grenade.

“Vance,” he said the moment he saw me, voice tight. “We need to talk about yesterday.”

“Later,” I said. “Leo’s missing.”

That stopped him.

He blinked. “What do you mean missing?”

Ms. Ruiz spoke calmly.

“Absent today. Concerning note on an assessment. Potential risk.”

The principal’s face drained.

You could almost see the gears turning.

Not the human gears.

The bureaucratic ones.

Liability. Reporting. Headlines.

He reached for his phone.

“I’ll call the attendance office,” he said.

“Call whoever you want,” I said. “But we’re going to his house.”

His mouth opened like he was about to say policy.

Then he looked at the quiz note again.

And whatever was left of his own humanity pushed through the paperwork.

“Okay,” he said, swallowing. “Okay. Go.”

Leo’s apartment complex was fifteen minutes from the school, behind a strip of tired storefronts and a cracked parking lot.

It was the kind of place you don’t notice unless you have to.

The kind of place kids live when grown-ups say they “just need to try harder.”

We walked up two flights of concrete stairs that smelled like old cooking oil and damp carpet.

Ms. Ruiz knocked.

No answer.

She knocked again, louder.

Still nothing.

I glanced at the window beside the door.

The blinds were half open.

Inside, I saw a flash of movement.

Just a shadow.

A quick shift.

Like someone ducking away.

My chest tightened.

“Leo,” Ms. Ruiz called gently. “It’s Ms. Ruiz. I’m here with Mr. Vance. We’re not in trouble. We just want to talk.”

Silence.

Then, finally, a sound.

The faint scrape of a lock.

The door opened a few inches.

Leo’s face appeared in the gap—pale, exhausted, eyes red-rimmed like he hadn’t slept since the last century.

The gray hoodie hung on him like a surrender flag.

He didn’t look surprised to see me.

He looked… ashamed.

Like he’d been caught needing something.

“Hey,” I said softly. “You didn’t come to class.”

He stared at the floor.

“My mom’s asleep,” he whispered.

Ms. Ruiz leaned in, gentle but firm.

“Leo,” she said, “are you safe right now?”

He swallowed.

“I don’t know,” he said.

Those three words were more frightening than screaming.

Because they were honest.

Inside, the apartment was dim and cluttered.

A couch with a blanket thrown over it.

A stack of overdue notices on the counter.

A fridge covered in magnets from places they probably never got to visit.

Leo’s mother was on the couch, breathing shallowly, an empty pill bottle on the coffee table—not dramatic, not criminal, just… sad. The kind of tired that turns into numbness.

Ms. Ruiz moved into professional mode immediately, calling for medical help, speaking calmly, using the language that keeps a situation steady.

I stayed with Leo in the small kitchen.

He leaned against the counter like his bones didn’t want to hold him up.

“I wasn’t trying to…” He struggled for words. “I wasn’t trying to be… dramatic.”

“I know,” I said.

He let out a laugh that sounded like it had broken glass in it.

“They’re always watching us,” he said suddenly, bitterness sharp. “The school apps. The trackers. The ‘wellness check-ins.’ They ask ‘How are you?’ and you click a face. Happy. Sad. Angry. Like it’s a game.”

He looked at me, eyes burning.

“But I didn’t write it there,” he said, tapping the quiz paper. “Because I wanted a robot to see it.”

I didn’t speak.

I didn’t fill the silence with a motivational quote.

I let him have the space.

“That note,” he whispered, voice cracking, “was for you.”

My throat tightened.

“Why?” I asked.

He shrugged, small and helpless.

“Because you’re the only one who… looks at my paper,” he said. “Like, actually looks.”

And there it was.

Not a debate.

Not a policy.

Not an algorithm.

A kid telling me the difference between being scanned and being seen.

Later that day, after Leo’s mom was taken to get care and Leo was with a safe adult—handled properly, responsibly, no hero fantasies—Ms. Ruiz and I returned to school.

The building buzzed like a disturbed hive.

My email inbox had exploded.

A district notice.

A meeting invite.

And a new memo with a bold title:

MANDATORY IMPLEMENTATION OF APEX-LEARNING FEATURES — EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY

Under it, a cheerful line that made my teeth grind:

“This will enhance student safety and ensure consistent instructional outcomes.”

Enhance student safety.

I wanted to throw the memo through a window.

Because the safest thing Leo had all week wasn’t a feature.

It was a tired old man with a red pen who still believed margins mattered.

At 4:00 p.m., the district held an emergency “listening session.”

That’s what they called it.

Listening, in their world, meant letting people talk and then doing what they already planned.

The auditorium was packed.

Teachers.

Parents.

A few students brave enough to show up.

Dr. Sterling stood on stage, smiling like a man selling an upgrade.

“We understand emotions are high,” he began. “But we must evolve. We must modernize. We must remove inconsistency.”

A parent stood up and shouted, “My kid needs results, not feelings!”

Another parent yelled back, “My kid needs a reason to stay alive!”

The room erupted.

That’s America right now, isn’t it?

Everyone desperate.

Everyone tired.

Everyone terrified they’re losing their children to something they can’t name.

Dr. Sterling raised his hands.

“This is exactly why we need systems,” he said. “Human judgment is unreliable.”

I stood up slowly.

My knees complained.

My back cracked.

But I stood anyway.

“I found a note in the margin of a quiz,” I said.

The room went quieter, like someone had turned down the volume.

“It wasn’t flagged,” I continued. “It wasn’t scanned. It wasn’t caught.”

I held up the paper—not showing the message in full, not turning a boy’s pain into content, just holding the evidence of something fragile.

“That note was written for a human,” I said. “Because a human is the only thing Leo trusted.”

Sterling’s smile tightened.

“We have safety features for that,” he said quickly. “With full implementation, the system—”

“The system didn’t catch pencil,” I said.

A murmur spread.

Sterling’s voice sharpened.

“Teachers cannot be the sole safety net,” he said. “You are not trained mental health professionals.”

“I didn’t diagnose him,” I said. “I noticed him.”

That line landed like a match.

Not because it was poetic.

Because every teacher in that room had, at some point, saved a kid by simply paying attention.

And every parent in that room knew what it felt like to pray someone would notice before it was too late.

Sterling stepped forward.

“Are you suggesting we abandon tools that increase efficiency and safety?” he asked.

I looked out at the crowd—parents with crossed arms, teachers with clenched jaws, students staring like they were watching adults decide the future of their lungs.

Then I said the thing that would guarantee comments for days:

“I’m suggesting this,” I said, voice steady. “If you want a frictionless school, you have to be honest about what you’re sanding away.”

Silence.

“A classroom isn’t an app,” I continued. “It’s a relationship. And relationships are messy. They take time. They require eye contact. They require adults who don’t look away when a kid is drowning.”

I pointed gently—not at Sterling, not at the district, but at the idea that everything can be optimized.

“If you remove the mess,” I said, “you remove the moments where a child dares to whisper the truth.”

I lowered the quiz.

“The truth is in the margins,” I said. “And the future that scares me isn’t technology.”

I paused, letting the words settle.

“The future that scares me is a world where we stop reading each other.”

After the meeting, the debate didn’t end.

It exploded.

Teachers argued in the parking lot.

Parents argued online.

Students argued in group chats.

Some people demanded full AI everything.

Some people demanded a ban on devices.

Some people blamed teachers.

Some people blamed parents.

Some people blamed “kids these days.”

And the kid at the center of it all—Leo—just wanted someone to ask him one simple question without turning it into a war:

Are you still here?

That night, I sat at my kitchen table with a stack of blank index cards.

I wrote one sentence on top of each:

“Tell me something you can’t say out loud.”

The next day, I gave them to my students.

“No names,” I told them. “No grades. Just truth.”

Some kids rolled their eyes.

Some laughed.

Then the room went quiet.

Not the dead, humming auditorium quiet.

The alive quiet.

The kind of silence where something real is being born.

By the end of class, the cards were in a pile on my desk like fallen leaves.

I didn’t read them immediately.

I just held the stack.

Because even without reading a single word, I could feel the weight of them.

That weight wasn’t data.

It was humanity.

And here’s the message I wish someone would tattoo on every screen we hand a child:

Speed is not the same as care.

Efficiency is not the same as love.

And a system that can’t notice suffering will always call suffering an “outlier.”

If you want to argue, argue.

If you want to comment, comment.

But answer this honestly:

Would you rather your child be perfectly measured… or truly seen?